Code found here. I worked hand in hand with Tristan Frizza on this, and we had our questions both technical and directional patiently answered by Corey Lynch, Suraj Nair and Eric Jang.

Introduction

“Can we enable fast transfer learning to new scenes or behaviours by using language to structure a joint trajectory embedding space between robot specific data and much larger, diverse set of human video?”

Inspiration

We were inspired to ask this question by a pair of papers, Learning from play (LFP) and Grounding language in play (LangLMP). These present a couple of interesting ideas:

- In a long dataset of teleoperated ‘play’, you can sample any subsequence as training data for a goal conditioned policy which learns to go from arbitrary A to B. LFP shows that this is both more data efficient and effective than learning from discrete demonstrations because a few hours of teleoperated ‘play’ provides millions of overlapping subsequences, giving broader coverage and variability.

- Define a sampled trajectory as $ \tau = (a_0,s_0,a_1,s_1 .. a_T, s_T) $, and set the goal state to the final state $ (s_g = s_T) $. This trajectory is unlikely to be the optimal path from $ s_0 $ to $s_g $, it is only one of many. We can capture this multimodality using a seq-seq VAE. The encoder of the VAE maps the subsequence as a latent ‘trajectory’ vector $E(z | \tau ) $, which the decoder combines with the state and goal state at each timestep to choose an action $\pi(a |z,s_t, s_g)$. During training, they seek to maximise the log probability of the true actions from that sequence while minimizing the KL divergence between the $z$ distribution of the planner and encoder for each sample. At test time, a ‘planner’ samples a potential trajectory vector given the initial and end goal $P(z |s_0, s_g)$. During training, the actor tries to decode that specific way of achieving the goal - at test time, the actor decodes one of the many ways of achieving it. Use images rather than states as goals by embedding the image in a lower dimensional space with a CNN as a feature encoder.

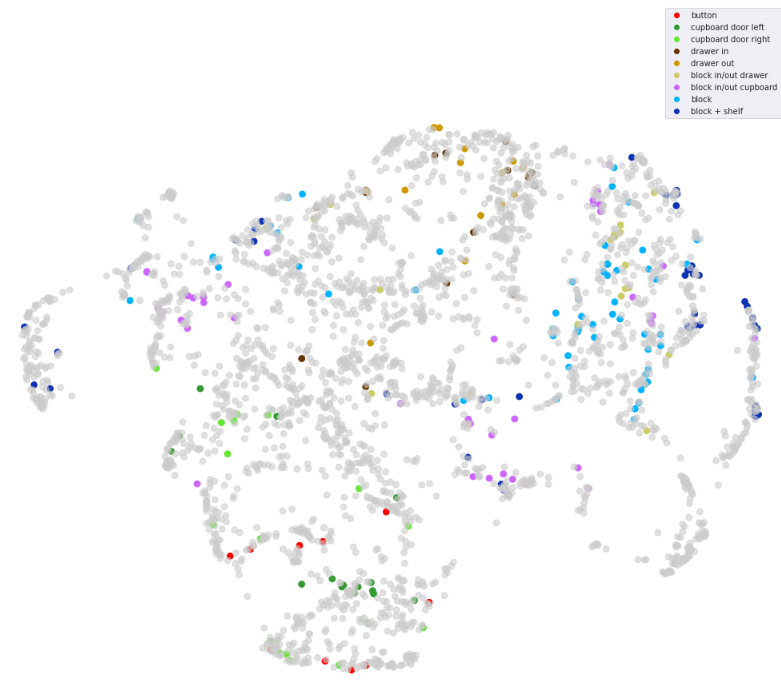

- The model can be adapted to use sentences as a goal by labelling a small (<1% of total dataset in their experiments) number of trajectories. Goal images and sentences will share the same goal embedding space because they will correspond to the same sequences of actions, which will be maximised for by the same imitation learning objective as before. This allows language to control the robot, while still learning more robust control from a vastly bigger dataset.

The question we are seeking to answer

We wondered whether you could facilitate transfer learning by similarly labelling a small number of videos from different contexts (e.g, human video) with sentences, then forcing the latent trajectory space to be structured around these so that similar behaviour across contexts is embedded in the same parts of the trajectory space. We initially imagined doing this with standard VAE reconstruction loss of the trajectories themselves (while you can’t reconstruct the actions for human video, you could have an additional head on the decoder which reconstructed the input images of both human and robot trajectories). In other words, noting that play learns good $p(a|s,g)$, can we learn $p(s’|s,g)$ or $p(s’|s,a)$ from more diverse but similarly rich data - and will this allow us to generalise better?

Corey advised that this could well work, and that their team had been interested in exploring a very similar idea by using contrastive learning to structure the latent space. In this case they would use the sentence embeddings of labelled trajectories to supply +ive/-ive pairs. This should both work better and is significantly less computationally intensive - so it is the approach we are pursuing.

Our hypothesis was that this would make it easier to transfer learn environments or behaviours outside the robot specific training data - as the feature encoder would be trained on a diverse array of inputs, and the trajectory space would be structured around behaviour and scenes outside the teleoperation dataset.

First step though? We had to build the tech stack up to that point - a good environment to teach a robot to play in, then reimplement LFP and LangLMP.

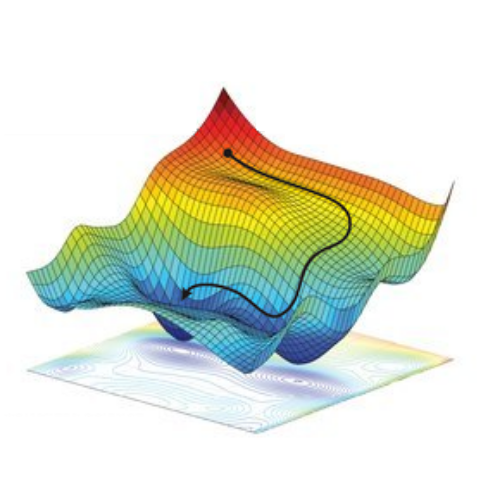

Before we get into it? Check out this gorgeous (but slightly under-regularised) embedding space of trajectories from recent experiments.

How hard can a great environment be?

Teleoperation

Insidiously hard. We tried re-implementing LFP for one of our senior year classes and failed due to a critical environment issue which we didn’t discover till we came back to crack our ‘great white whale’. Saving images of the environment took a variable amount of time, which was often long enough that it affected the frame rate of data capture. This meant that the time between actions in the dataset was variable, which meant that the time which the action was executed for was variable - decoupling the learnable link between action and outcome. We spent weeks trying to improve the algorithm itself - rather than making sure the environment was learnable. On the plus side, pyBullet offer’s great VR support!

Keep it simple

When we came back, we made sure to do it right. No cutting corners.

First, learn 3DOF reaching with scripted demonstrations. Then use scripted demonstrations to learn 3DOF pick/placing. Extend that to allow orientation control…

Next issue.

Representing orientation

What is the best way to represent orientation of the gripper? Corey et al use RPY - we thought we could be clever, and use quaternions to avoid the discontinuities inherent in RPY (typically at $ \pm \pi$). A fun fact about quaternions is that the negative of the quaternion is an equivlant representation of orientation. pyBullet is not consistent in the representation between timesteps. To correct this, you have to create a small check in the environment which checks if the sign on every element of the quaternion is the negative of the previous timestep, in which case - you flip the sign and thus smooth the signal.

Problem solved? Not quite. Quaternions must be normalised to be a valid orientation. Neural net outputs have no such constraint, besides, we still had a few discontinuities. This led us down the path of 5D and 6D rotational embeddings…

Hold up! We had been playing with too many satellites. Does a robot’s end effector really need to go beyond $ \pm \pi$ in any axis of rotation? Will it ever encounter a discontinuity? Not unless you’re trying to imitation learn off Houdini. We already had a link positioned at the tips of the gripper for inverse kinematics purposes - all you need to do is rotate that so that it is at 0,0,0 RPY in the arm’s default pose.

Long story short - RPY orientation control worked far better. Simplicity wins.

Next steps

The basline reimplementation of LFP works ok - it often achieves complex, two step goals but still fails too often to be a useful baseline for the questions we want to answer. We are still trying to nail down performance here.

We’re comparing 3 architectures. Encoder-actor which uses the $z$ from the full input trajectory as an input into the actor (in VAE terms, the decoder), planner-actor uses the ‘guessed’ $z$ from the initial and goal state, and goal conditioned behavioural cloning (GCBC) does not take an trajectory embedding as input, $\pi(a |s_t, s_g)$. The trade off between reconstruction loss and the KL divergence between the encoder and planner $z$ is controlled by a weighting $\beta$. $\beta = 0$ means there is no KL divergence loss term which results in an under regularised latent space where the encoder-actor reconstructs perfectly, but the planner’s outputs are meaningless and thus planner-actor fails. High values of $\beta$ means the latent space suffers mode collapse and becomes equivalent to GCBC (all $z$ are meaningless). This occurs because the actor always has access to $s_g$ and is autoregressive, which removes much of the multimodality once the trajectory has begun.

The right value of beta is low enough that the latent space is used, but high enough that the planner and encoder map to each other. In practise, this is tricky to get right, and action reconstruction loss does not provide the best guide to ultimate performance. We found that the reconstruction loss of GCBC was the lower bound for the performance of planner-actor, it didn’t get better than a fully collapsed latent space. In practise, this model can’t cope with the multimodality of potential behaviour. We found models with slightly worse planner-actor reconstruction loss, but much better encoder-actor reconstruction loss performed the best. In short, during training the planner might not have selected the particular ‘trajectory’ / $z$ which actually occured and therefore the reconstruction loss may not be perfect, but it maps to a part of the latent space where any of the $z$ which it does select are an effective way to complete the goal. One curiosity we’ve noticed is that a probabilistic actor (where the log likilihood of actions is minimised under a action distribution which is a mixture of 3 beta distributions) maintains structure in the latent space for much better planner-actor reconstruction loss values than a deterministic actor (where the MSE of actions is minimised, and the actor output is just a single vector).

Corey et al used a constant value of B=0.01 to weight the KL divergence. Initially they used the KL annealing trick from Bowman et al, which we have still found to be the best approach on our dataset. We’ve also explored cyclical annealing and learning a nicely regularised encoder space with info-VAE then mapping the planner directly to it.

In another divergence with their architecture, we found that we found that a determinsitic actor performed better despite the worse trajectory latent space. A probabilistic actor introduced noise which often destabilised the trajectories. Cory did mention that in experiments where they replaced the actor LSTM with a transformer they had to use a deterministic action output for training stability. A probabilistic actor is not strictly necessary because the planned trajectory encoding captures some multimodality and once as noted earlier once the sequence has begun further ambiguity is removed, but it is concerning that our model can’t recover from the small amounts of noise introduced.

Another issue is gripper loss, which is is currently 10x higher than any other dimension in the action space. We suspected this is because the gripper is much more discontinuous than the other actions, and tried a smoother ‘close’ over more timesteps (as is visibile in the videos from LFP and LangLFP) - but haven’t noticed an increase in performance. Furthermore, there is often a trade off between gripper performance and position/orientation performance as the trajectory space is regularised - which is curious. We think this is the key remaining environment fix. Other thoughts include casting a ray from one gripper tip to the other, letting to know if something is between the tips. This was inspired by Asymmetric self-play for automatic goal discovery in robotic manipulation, where they use a extra features to assist learning (relative distance and contact yes/no with each object). Those features aren’t feasible on a real robot, but an IR sensor on the gripper tip would be - and would give a degree of ‘proprioception’.

Next steps - more data, nailing the right beta value/schedule and exploring better grippers. We’d like much more robust performance before trying to learn on real robots.