- Introduction

- What is Hierarchial Reinforcement Learning?

- Analysing Learning Multi-Level Hierarchies with Hindsight (HAC)

- Relay Policy Learning

Introduction

Hierarchial Reinforcment Learning (HRL) carries unrealised promise. Using one model to break difficult, long time horizon goals into piecemeal, achievable goals handled by a different model should make solving tasks easier. It parallels the way we approach tasks. We do not think at the level of individual muscle fibres, but consider abstract goals which are broken into a sequence of stages that are then carried out by the motor cortex.

Hierarchy directly addresses two fundamental challenges in RL over long time horizons, credit assignment and exploration. All modern RL algorithms in continuous domains fail as the time resolution approaches zero because it becomes impossible to discern which actions in which states led to the positive or negative outcomes. Similarly, structuring and correlating exploration is critical, which is more difficult as temporal extent increases.

Despite this, it has largely failed to deliver on the hype. No major results use HRL, and recent work has found that even state of the art HRL algorithms amount to better exploration schemes. Indeed, OpenAI commented following their landmark DOTA results, that hierarchy simply proved unnecessary.

“RL researchers (including ourselves) have generally believed that long time horizons would require fundamentally new advances, such as hierarchical reinforcement learning. Our results suggest that we haven’t been giving today’s algorithms enough credit — at least when they’re run at sufficient scale and with a reasonable way of exploring.”

Two pieces of work made me interested in exploring whether this was about to change.

-

Relay Policy Learning (RPL), by Gupta et al achieved state of the art robotic manipulation results by training a two layer hierarchy with behavioural cloning fine-tuned with RL. They find hierarchially decomposing the problem makes it more amenable to RL finetuning than a flat policy would be.

-

Learning Multi-Level Hierarchies with Hindsight (HAC), by Levy et al is an elegant approach to training hierarchial models based on hindsight experience replay (HER) which solves the issue of non stationary lower levels. They achieve results on a set of simple problems that exceed non-hierarchial models.

I decided to try extend RPL by using off policy, hindsight based learning, which should be significantly more sample efficient than the on policy learning used in RPL and potentially make it viable for real world robotics.

This blog post uses two test environments. In the first a pointmass must push a block to a target position . This is an ideal testing environment because it is fast to train but contains basic versions of the difficulties facing robotic manipulation tasks (namely, that working out how to even manipulate the block requires significant exploration of the environment). Unfortunately, I failed to succeed at more complex environments, such as the same task but with multiple blocks and my robotic manipulation environment, but hey, RL is hard. The most likely issue is that the off-policy HRL framework I am using is too unstable compared to the on-policy algorithm used in RPL. With the recent release of the architecture specifics and simulation environment of RPL I plan to revisit this.

As it is, hierarchial reinforcement learning did produce significantly better results on the environment - but my experiments agree that it does not provide benefits beyond better exploration, nor does it increase the complexity of environment tackleable. This is by no means the final word on HRL, but how easy and effective reimplementing the work is gives a good idea of how robust the area is. In supervised learning - particularly in vision, many models will happily learn past hyperparameter and architectural differences, while in RL the random seed can sometimes cause failure!

What is Hierarchial Reinforcement Learning?

The Gradient published an excellent overview.

RL Refresher

As a quick refresher, the standard formulation of RL involves an environment with transition function $P(s_{t+1} | s_t, a_t)$, where $s_t$ and $a_t$ are the states and actions at timestep t, and $r_t$ = $R(s_t, a_t)$ is the reward function. The goal is to find a policy $\pi(a | s)$ which maximises the expected sum of rewards over each trajectory $E_{\pi} ( \sum_{t=0}^T \gamma^t R(s_t, a_t) )$.

Goal conditioned RL extends this by making a goal state (or subset of the state), $s_g$, an input of both the policy and the reward function, $\pi(a | s, s_g)$, $r_t = R(s_t, s_g) $. This allows one policy to be trained to reach different goals from the same environment.

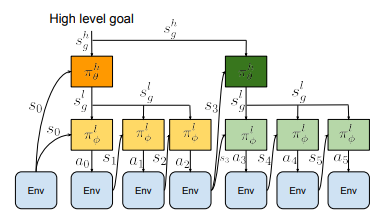

Hierarchy

Broadly, HRL consists of two or more models, where the lowest model acts at the full time frequency of and in the action space of the environment, while higher levels act less frequently and command lower levels to carry out behaviours or reach subgoals. Behaviours can be defined in a continuous space through latent variables, or more distinctly by selecting from a set of learnt action primitives through one-hot options. Similarly, goals can be defined through latent variables or the full observation space of the environment.

Encoding behaviours into latent space is clearly more effective than a sparse set of options, as it allows behaviours to be composed for new problems. It is also an interesting way of discovering a diverse array of behaviour. However, its difficult to specify and debug learning here, and all layers must be learnt in concert. I’ve personally found the results of work in this vein difficult to recreate in the past.

Latent representations of goal states are useful in image domains because they free the lower levels to focus on only goal critical aspects of the environment, which follows a broader theme that reconstruction based representation learning is less effective than contrastive learning - because reconstruction is unnecesarily difficult and often focuses on irrelevant parts of the image.

When state space is available, specifying goals here is easy, inexpensive to compute and by using HAC we can train the layers of the hierarchy independently. In addition, it is easy to use unlabelled interaction data to pretrain via RPL.

Analysing Learning Multi-Level Hierarchies with Hindsight (HAC)

Hindsight

HAC extends Hindsight Experience Replay (HER) to the hierarchial setting.

HER allows goal conditioned sparse reward environments to be efficiently solved by off-policy algorithms. Sparse rewards give 0 for success and -1 for failure, while dense rewards resemble a continuous function, such as euclidean distance between the current state and the goal state. Sparse rewards are preferred to dense rewards because dense rewards can contain local minima and require time consuming design. However, dense rewards guide an agent gradually through the environment, unlike with sparse rewards where an agent only receives signal when it succeeds, meaning that at first it randomly fails until it accidentally succeeds.

HER provides more signal by replacing the desired goal with the goal achieved at the end of each trajectory. This means that even if the agent never achieves the desired goal in any trajectory (such as placing a block in the commanded position), it learns how to succeed at other potential goals (by knocking the block into them accidentally). This becomes a natural curriculum that leads the agent to learn how to succeed at more and more precise goals.

Hierarchial Actor Critic

HAC uses hindsight of both the action and the goal to train each level of the hierarchy independently. Typically even if the higher level is setting the correct subgoals, if lower levels are unable to achieve them, the higher level will learn that that they are incorrect for reaching the ultimate goal. Furthermore, because the lower levels are training, the behaviour will always be different and the higher level will be unable to learn any relation between the subgoals it outputs and where the agent ends up - the issue of non stationarity.

To solve this, in the $(s, a, s’, r, s_g)$ tuple recorded by the higher level replay buffer, HAC substitutes the action (i.e, the subgoal commanded) with the state that was actually achieved by the lower level. This means that the model is always training as though the lower level is perfect at achieving the goals set, and learns the correct relationship between goals set and progress toward the ultimate goal.

This is a more elegant approach than their original idea, which was to penalise the higher level for setting unreachable subgoals, and may have been inspired by the HER+HRL request for research. As they found and we will confirm, a small amount of this ‘subgoal testing’ is still required, as while the model should learn the correct value for states that are ultimately reachable by the lower level, the model can overestimate the value of genuinely unreachable goals (for example, coordinates within walls), because action substitution means they never appear in the replay buffer.

So, lets take a look at the impact of HAC - and what it takes to make it work.

- How much can hierarchy improve learning over a flat model, at what kind of time horizon?

- What kind of subgoal performs best? Is it the full state of the environment, just the goal relevant dimensions, or just the directly controllable dimensions corresponding to the agent itself?

- What is the higher level learning?

- Is subgoal testing required?

- Does hierarchy provide benefits beyond better exploration?

Quick Algorithm Details

All models are trained with Soft Actor Critic and Hindsight experience replay for a fair comparison between hierarchial and nonhierarchial models. We only investigate two level hierarchies, as RPL found this sufficient for complex manipulation. All models are 3 layer MLPs with 256 neurons in per layer.

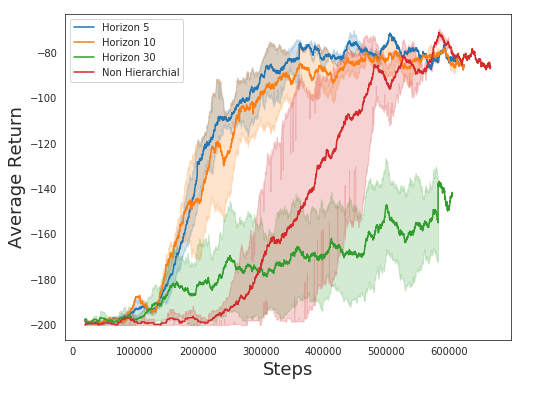

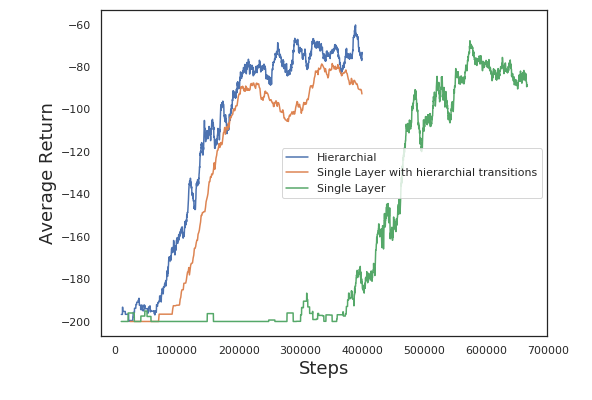

Performance over Time Horizons

How often should the higher level reset the subgoal which the lower level is trying to reach? If it is every timestep, then this eliminates the expected advantages of hierarchy, but if it is too infreqent, then the model may not adapt to new circumstances effectively or explore diversely enough within each trajectory. On this problem, a new subgoal every 5 timesteps appears to be ideal, learning 2-3x as fast as a nonhierarchial baseline.

What kind of Subgoal performs best?

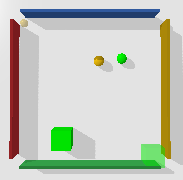

On the left, subgoals in the full environment state are visualised - with the transparent pointmass and block visualising the subgoal. On the right, subgoals exclusively in the controllable dimensions of the environment are visualised - only the pointmass itself. In the center, a non hierarchial model without subgoals is shown.

If the subgoal is exclusively pointmass position, then the lower level should learn extremely quickly as this is an easy task. However, this has the disadvantage that the lower level is not considering the intended position of the block as it acts. By including block position in the subgoal, you avoid this issue but make the lower level’s task significantly more complex.

I found that a subgoal consisting exclusively of the pointmass gave benefits to hierarchy, while a full state subgoal (or a subgoal including only the block position and not the mass positioin) was worse than solving the task non-hierarchially - even when piecewise rewards for the mass and block were implemented. In fact, the full state subgoal on the left had to be trained using relay learning - where it was the best performer.

Visualising Subgoal Value

When using just the next position of the pointmass as a subgoal, we can visualise the expected value of every possible next position at any given state by passing them into the Q function (i.e the critic, Q(s,a)) of the higher level model. This lets us clearly visualise that the higher level is learning the correct behaviour. It assigns high value to the opposite side of the block to the goal, and low value around the block once it has placed it into the goal position.

Subgoal Testing

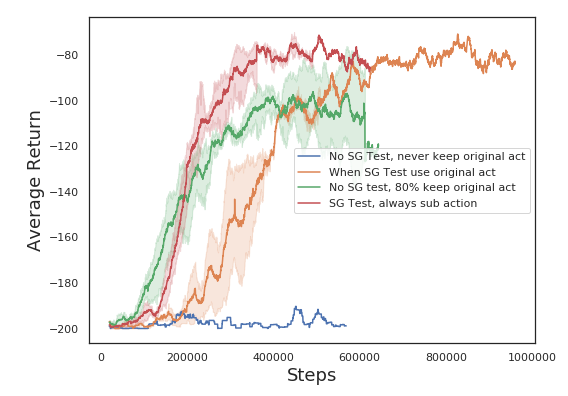

As described earlier, by substituting the lower level achieved goal for the subgoal (higher level action) in the replay buffer, the higher level trains as though the lower level perfectly achieves the subgoals it commands. However, this will lead to the higher level assigning unknown value to states which are never reached, even if they are commanded. Levy et al’s solution is to periodically set the lower level policy to deterministic instead of stochastic, not substitute the subgoal for the achieved goal and then assign a large negative reward to transitions where the higher level policy sets unreached subgoals. I wondered if instead, it would be sufficient to simply not subsitute subgoal for achieved goal some fraction of the time, so that the model would learn that unreached goals do not progress it towards the goal.

As expected, if we never keep the original action and don’t directly penalise unreached subgoals, the model proposes impossible subgoals because each time it sets one, the replay buffer only sees the goal that was actually reached - not the proposed impossible goal. This totally fails to learn.

Surprisingly, subgoal testing with the achieved goal instead of the original goal performs best. This is truly bizzare, and actually arose from a bug in my code where I was still subsituting the action when subgoal testing. What should perform best is subgoal testing, but with the action that was unreachable kept and penalized, instead of subsituted.

Benefits beyond Exploration

Ofir et al, in Why does Hierarchy (Sometimes) Work So Well in Reinforcement Learning, train a ‘shadow learner’, a single layer policy trained on the transitions collected by the hierarchial policy (using their algorithm HIRO). They do this to disentangle the benefits of HRL for exploration and modelling capacity. My results here match theirs - there is no significant difference when the models are trained with the same transitions. As it stands, the benefit of HRL is in exploration.

Relay Policy Learning

Relay Policy Learning (RPL) uses the same two layer, goal conditioned hierarchial policy, but pretrains both layers with supervised learning from expert demonstrations based on the goal relabelling they used in Learning from Play (LFP) . Rather than assuming demonstration data must correspond to a desired task, in demos they interact widely with the environment and regard any state reached along these trajectories as a potential goal. For our purposes we can use a model we’ve already trained to collect demonstration data, rather than teleoperating.

To create higher level training data, they sample a sub-trajectory from the data and take the final state as the goal state. If the higher level acts every n steps, then observation, action pairs are simply $(o_t, a_{t+n})$ for all timesteps t throughout the trajectory. Lower level training data takes windows from $t$ to $t+n$ from the trajectories, and sets $s_{t+n}$ as the goal state, using every timestep within each window as data.

This greatly expands the available data, because each observed state, action pair is valid for many goals. It also makes the data significantly easier to collect for a human teleoperator, as instead of having to reset the environment after each demonstration - the human can freely play. In LFP they found that models purely trained using supervised learning were able to comfortably complete a variety of robotic manipulation tasks.

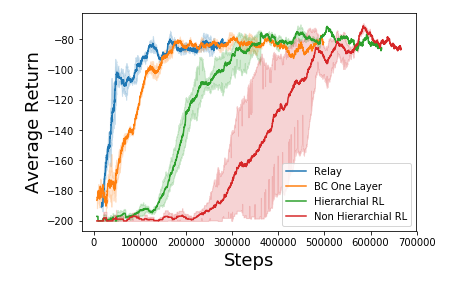

In RPL, they take the goal conditioned behavioural cloning model (GCBC) from LFP, make it hierarchial and finetune only the lower level model. They found this sufficient for very long horizon robotics tasks. They used a variant of TRPO, but here I used HAC from above, which should be both more efficient and better suited for the sparse rewards of manipulation tasks - but less stable as noted.

The training is composed of two parts, firstly the inital pretraining using supervised learning, then training with a combination of the supervised and reinforcement learning losses. The supervised loss was trialled with both MSE and maximising logliklihood of target actions under the actor distribution - and MSE performed better. This is likely because I’m only working with a single normal distribution per dimension as the action distribution - rather than a potentially multimodal mixture of distributions as they do. However, in a previous attempt to implement LFP I used mixtures of 3 beta distributions - and MSE still performed better. I’m extremely curious what error I’m making - it might have significant impact on the complexity of behaviour capable of being learnt by the pretrained model.

Pretrained Baseline

The pretrained baselines did learn to complete the task sometimes, but not reliably or efficiently as seen by the average reward and visualisations of the models below.

| Subgoal Components | Reward for Pretrained Models |

|---|---|

| Block | -193.80689655172415 0.0896551724137931 |

| Point Mass | -178.09558823529412 0.3014705882352941 |

| Point Mass and Block | -166.472 |

RL Finetuning

By introducing the HAC finetuning on the lower level, our Relay learning model learns to solve the full task with equivalent performance to all other models, but in many less update steps. It is even more efficient, with 10x less expert demonstrations than behavioural cloning on a nonhierarchial model (2000 timesteps of expert demonstration, vs 20000 timesteps of expert demonstration).

At what level of complexity do our models tap out?

Multi Block

The next step in environment complexity is to add another block with its own goal location. We can collect expert demonstrations for this by using a model trained to perform the task with one block - and indexing the state and goal input so that it only recieves the information on the state and goal of one block at a time. While this does mean the agent won’t account for the other block as it moves the current block - if we just discard any demonstrations where both blocks are not at the target location in the final timestep we can collect great baseline demonstrations.

What is interesting is that even with expert demonstrations, both our relay and flat models completely fail to learn to move either of the blocks to the goal. To encourage this, I made the reward piecewise - so that it would recieve +1 for each block on target. Our intuition would expect that it would be capable of learning to complete one of the blocks per run in this case - even if both is too long of a time horizon. It raises an interesting question - why is this so much harder? One aspect is that the state dimension has increased from 8 to 12 $(x_{pos}, y_{pos}, x_{vel}, y_{vel})$ , and the goal dimension has increased by 2 $(x_{pos}, y_{pos})$. The time horizon required to complete both tasks is double that of the single task - but why doesn’t it learn to complete what it can regardless?

Robotics Environments

As expected, the algorithms solve the Panda Reaching environment within a few thousand steps in the environment. Reaching is an extremely easy task with hindsight because every state reached modifies the achieved goal. Unfortunately they fail to learn pushing and pick and place tasks despite scripted expert demonstations.

In past experiments, I found that OpenAI’s baseline implementation of HER+DDPG with Behavioural Cloning is capable of learning even a difficult tool usage environment I created. My RL algorithms (which are effectively wrappers around the Spinning Up implementation of SAC and TD3) cannot. Both of these are ostensibly stronger algorithms than DDPG - and both successfully learn the pointmass and block task but fail to scale to more complex tasks. This could lie in the implementations of the RL algorithms themselves, or in how I am integrating supervised losses. With the release of Stable Baselines 3, I’d like to look into how other RL implementations perform - and modify them to include include supervised losses from demonstration.

Conclusion

Hierarchial RL does appear to offer benefits over flat policies due to better exploration, and it does benefit well from supervised pretraining. However, I haven’t found that it increases the complexity nor time horizon of tackleable environments, nor are the benefits currently worth the extra complexity and hyperparameter tuning. The most powerful RL implementation for manipulation tasks which I have found is the flat DDPG+HER+BC, which none of my experiments have managed to superceed. This is by no means the definitive word on hierarchial learning - but based on the results of these experiments I am currently more interested in looking at better exploration strategies, or decomposing problems hierarchially by combining planning based methods with RL which has seen recent promise.

I’d love any feedback you have on this piece. In particular, I’d love to know if the level of detail + referring to outside sources is appropriate, or if more explaination is necessary.